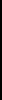

King William I The Conqueror - Quick Stats

Born: c 1028, Falaise, Normandy, France

William the Conqueror: The First Norman King of England

William I, more famously known as William the Conqueror, stands as one of the most significant figures in medieval history. His conquest of England in 1066 altered the trajectory of the nation, marking the end of the Anglo-Saxon era and the beginning of Norman rule. A skilled warrior, a shrewd politician, and an effective administrator, William shaped England into a centralized, feudal kingdom while leaving a lasting imprint on its language, culture, and governance. This article delves deeply into the remarkable life and reign of William, exploring his rise to power, the conquest of England, his governance, and his enduring legacy.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Born in Falaise, Normandy, around 1028, William entered the world under challenging circumstances. As the illegitimate son of Robert I, Duke of Normandy, and Herleva, the daughter of a tanner, William's birth earned him the moniker "William the Bastard." Despite the societal stigma of illegitimacy, his father recognized him as his heir, a decision that would shape Williamís destiny.

Born in Falaise, Normandy, around 1028, William entered the world under challenging circumstances. As the illegitimate son of Robert I, Duke of Normandy, and Herleva, the daughter of a tanner, William's birth earned him the moniker "William the Bastard." Despite the societal stigma of illegitimacy, his father recognized him as his heir, a decision that would shape Williamís destiny.

When Robert died unexpectedly in 1035 during a pilgrimage, young William inherited the dukedom of Normandy at the age of eight. His succession immediately plunged the region into chaos. Noble factions and rival claimants sought to exploit his youth and illegitimacy, leading to years of instability and violence. Assassinations of Williamís guardians and protectors were common, leaving him to navigate a dangerous political landscape.

The decisive Battle of Hastings occurred on October 14, 1066. Haroldís forces, composed of experienced housecarls and the fyrd (local militia), adopted a strong defensive position on Senlac Hill. Williamís army, utilizing cavalry, archers, and infantry, launched a series of assaults. The Normans employed tactical innovations, such as feigned retreats, to break the cohesion of the English shield wall. After hours of fierce combat, Harold was killedóaccording to tradition, by an arrow to the eyeóand his army was routed.

Despite these early challenges, William demonstrated exceptional resilience. As he matured, he emerged as a capable leader and military commander. By the 1040s, he had consolidated his power in Normandy, defeating rebellious barons and restoring stability to the duchy. His strength as a ruler was further enhanced by his marriage to Matilda of Flanders around 1051, a union that bolstered his political standing and secured an alliance with a powerful neighboring territory.

Wife: Matilda of Flanders

Father: Robert I, Duke of Normandy

Mother: Herleva (also known as Arlette of Falaise)

Died: September 9, 1087, Rouen, Normandy, France

The Claim to the English Throne

Williamís connection to the English throne arose from his relationship with Edward the Confessor, the Anglo-Saxon king of England. Edward, who had spent years in exile in Normandy before becoming king, maintained close ties to Norman culture and its ruling elite. Norman sources assert that Edward promised William the throne, recognizing his strength and shared cultural ties.

Williamís connection to the English throne arose from his relationship with Edward the Confessor, the Anglo-Saxon king of England. Edward, who had spent years in exile in Normandy before becoming king, maintained close ties to Norman culture and its ruling elite. Norman sources assert that Edward promised William the throne, recognizing his strength and shared cultural ties.

A pivotal moment came in 1064 when Harold Godwinson, the Earl of Wessex and one of Englandís most powerful nobles, was shipwrecked on the Norman coast. Harold was brought to Williamís court, where he allegedly swore an oath of fealty to support Williamís claim to the English throne. While this event is heavily disputedóparticularly by Anglo-Saxon chroniclersóit became a central justification for Williamís invasion of England.

When Edward the Confessor died on January 5, 1066, Harold was crowned king with the support of the English nobility. William viewed this as a betrayal and a direct challenge to his legitimacy, prompting him to prepare for an invasion.

Consolidating Power

Williamís coronation as King of England on Christmas Day 1066 at Westminster Abbey was a moment of triumph, but his position remained precarious. Over the next several years, he faced numerous uprisings and challenges to his rule, particularly in the north of England, where resistance to Norman control was fierce.

Williamís coronation as King of England on Christmas Day 1066 at Westminster Abbey was a moment of triumph, but his position remained precarious. Over the next several years, he faced numerous uprisings and challenges to his rule, particularly in the north of England, where resistance to Norman control was fierce.

Williamís claim to the throne was not solely based on promises or oaths; it was also rooted in a broader vision of Norman expansion and consolidation. The prospect of ruling England represented not just personal ambition but an opportunity to extend Norman influence and secure a lasting legacy.

The Norman Conquest

Williamís preparation for the invasion of England was a monumental undertaking. He gathered an army of approximately 7,000 men, including cavalry, infantry, and archers, and secured the blessing of Pope Alexander II, who endorsed his claim to the English throne. The papal support added a moral and religious dimension to his campaign, framing it as a divinely sanctioned mission.

Williamís preparation for the invasion of England was a monumental undertaking. He gathered an army of approximately 7,000 men, including cavalry, infantry, and archers, and secured the blessing of Pope Alexander II, who endorsed his claim to the English throne. The papal support added a moral and religious dimension to his campaign, framing it as a divinely sanctioned mission.

On September 28, 1066, Williamís fleet landed at Pevensey on the southern coast of England. Establishing a foothold, he began advancing inland, seizing towns and fortifying his position. Harold, meanwhile, had just defeated a Viking invasion led by Harald Hardrada at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in the north. Exhausted and with his army depleted, Harold marched south to confront the Normans.

One of the most infamous episodes of Williamís reign was the "Harrying of the North" (1069Ė1070). In response to rebellions and incursions from Scandinavian forces, William ordered a brutal campaign to subdue the region. Villages were burned, crops destroyed, and livestock slaughtered, causing widespread famine and devastation. While the campaign succeeded in suppressing rebellion, it left a lasting scar on the north and demonstrated the harsh measures William was willing to employ to maintain control.

Predecessor: Harold II

Successor: William II (William Rufus)

Williamís rise to power also coincided with a period of political fragmentation and shifting alliances across Europe. Normandy was a crucial player in this landscape, and Williamís ability to navigate the complex web of feudal loyalties and rivalries solidified his position not just as a regional power but as a figure of continental significance.

Governance and Administrative Reforms

Williamís reign was marked by significant administrative reforms that laid the groundwork for medieval Englandís governance. The introduction of the feudal system transformed the kingdomís political and economic structure. Under this system, land was granted to nobles in exchange for military service, creating a hierarchy of loyalty and obligation that extended from the king to the lowest serf.

Williamís reign was marked by significant administrative reforms that laid the groundwork for medieval Englandís governance. The introduction of the feudal system transformed the kingdomís political and economic structure. Under this system, land was granted to nobles in exchange for military service, creating a hierarchy of loyalty and obligation that extended from the king to the lowest serf.

William also sought to integrate England into the broader Norman and European cultural sphere. The Norman Conquest introduced the French language, which became the language of the court and administration, influencing the development of Middle English. Norman architecture, characterized by its grand scale and distinctive style, reshaped the English landscape.

In addition to these structural changes, William worked to strengthen ties between England and the papacy, ensuring that the church played a central role in legitimizing his rule. The construction of monasteries and cathedrals reflected both his piety and his commitment to establishing a stable, unified realm under Norman leadership.

Death and Legacy

In 1087, while campaigning in France, William suffered fatal injuries during the siege of Mantes. He died on September 9, 1087, in Rouen and was buried in the Abbey of Saint-…tienne in Caen, Normandy. His death marked the end of a transformative reign that reshaped England and its relationship with the rest of Europe.

In 1087, while campaigning in France, William suffered fatal injuries during the siege of Mantes. He died on September 9, 1087, in Rouen and was buried in the Abbey of Saint-…tienne in Caen, Normandy. His death marked the end of a transformative reign that reshaped England and its relationship with the rest of Europe.

Williamís legacy is profound. As the first Norman king of England, he established a centralized monarchy that set the stage for the evolution of English governance. The cultural and linguistic changes introduced during his reign had a lasting impact, blending Anglo-Saxon and Norman traditions into a unique English identity.

This victory cemented Williamís claim to the English throne, but it also marked the beginning of a challenging period of consolidation and resistance. The Norman Conquest was not merely a military triumph; it was a transformative event that reshaped Englandís political and cultural landscape.

To secure his rule, William replaced the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy with Norman nobles, redistributing land and wealth to his loyal followers. This shift created a new ruling class and fundamentally altered Englandís social and political landscape. The construction of castles, including the Tower of London, became a hallmark of Norman dominance, serving both as military strongholds and symbols of authority.

William also implemented reforms to centralize power and ensure the loyalty of his vassals. The feudal system he established created a hierarchy of obligations and loyalties, binding the nobility to the crown in exchange for land and privileges. This system not only secured Williamís rule but also laid the foundation for the governance of medieval England.

One of Williamís most notable achievements was the commissioning of the Domesday Book in 1086. This extensive survey recorded land ownership, resources, and population across England, providing a detailed snapshot of the kingdomís wealth and structure. The Domesday Book was a revolutionary administrative tool, enabling William to effectively manage taxation and governance.

While his reign was often characterized by brutality, Williamís administrative and military achievements were groundbreaking. He transformed England into a feudal state, ensuring stability and laying the foundations for future growth. His conquest and rule are often seen as a turning point in English history, marking the end of one era and the beginning of another.

Conclusion

William the Conquerorís life and reign epitomize ambition, resilience, and transformation. From his precarious beginnings as an illegitimate child to his triumph at Hastings and his effective rule as King of England, Williamís story is one of determination and enduring influence. His legacy, etched into the fabric of English history, continues to shape the nationís identity and institutions to this day. William the Conqueror remains a pivotal figure in medieval history, a testament to the power of vision

William the Conquerorís life and reign epitomize ambition, resilience, and transformation. From his precarious beginnings as an illegitimate child to his triumph at Hastings and his effective rule as King of England, Williamís story is one of determination and enduring influence. His legacy, etched into the fabric of English history, continues to shape the nationís identity and institutions to this day. William the Conqueror remains a pivotal figure in medieval history, a testament to the power of vision

Children: Robert Curthose (Duke of Normandy)

Richard (Died Young)

William II (King of England)

Henry I (King of England)

Adela of Normandy (Mother of Stephen of

Blois, Future King of England)

Cecilia (Abbess of Holy Trinity in Caen)