The Roman Invasion of Britain and the Subsequent Campaigns

The Roman invasion of Britain marked a turning point in the island's history. Long viewed by the Romans as a distant and mysterious land, Britain was initially bypassed during Julius Caesarís campaigns in Gaul, but by the first century AD, the island's resources and strategic importance drew renewed Roman attention. The successful invasion of AD 43, initiated by Emperor Claudius, brought much of Britain into the Roman Empire, but the conquest was neither swift nor easy. The occupation required decades of military campaigns led by a series of Roman generals and governors. Each of these leaders played a crucial role in expanding and consolidating Roman control, often through brutal campaigns against the native tribes.

Claudius and the Initial Invasion (AD 43)

The invasion of Britain in AD 43 was launched under the direction of Emperor Claudius, who sought to secure a military victory to solidify his political position in Rome. Claudius faced internal challenges to his rule and saw the conquest of Britain as a way to bolster his legitimacy and prestige. The decision to invade was also driven by economic and strategic factors, as Britain was known for its valuable resources, including metals like tin and lead.

The invasion force consisted of approximately 40,000 men, including four legionsóLegio II Augusta, Legio IX Hispana, Legio XIV Gemina, and Legio XX Valeria Victrixóalong with auxiliary troops. The army was led by Aulus Plautius, an experienced general who had previously served in the Balkans. The Roman fleet transported the forces across the English Channel, landing near modern-day Kent

Upon landing, the Romans faced resistance from the native tribes, particularly the Catuvellauni, led by their kings, Togodumnus and Caratacus. The initial battles were hard-fought, but the Romans, with their superior military organization, began to gain the upper hand. The turning point came when the Romans crossed the River Thames and defeated the British forces at a significant battle near the Medway. Togodumnus was killed, but Caratacus escaped and continued to resist Roman rule for several years.

After securing these early victories, Aulus Plautius halted his advance and awaited the arrival of Claudius. The emperor arrived with reinforcements, including war elephants, and led a ceremonial march into the newly conquered territory. Claudius accepted the submission of several British tribes and declared the province of Britannia established. He returned to Rome soon after, leaving Plautius to oversee the pacification of the region.

The Campaigns of Aulus Plautius (AD 43-47)

Following Claudius's departure, Aulus Plautius remained in Britain as the first Roman governor of the new province. His task was to secure Roman control over the southeastern tribes and establish administrative centers. The Catuvellauni, the dominant tribe in the southeast, were effectively subdued, and their capital at Camulodunum (modern Colchester) was transformed into a Roman colonia.

Plautius spent the next few years consolidating Roman power, dealing with sporadic resistance from various tribes. One of his notable achievements was securing alliances with certain tribes, such as the Iceni in eastern Britain, who would later become important allies. By AD 47, Roman control over southern Britain was relatively stable, and Plautius was recalled to Rome

The Campaigns of Ostorius Scapula (AD 47-52)

Ostorius Scapula succeeded Plautius as governor of Britain. His tenure was marked by renewed military activity, particularly in the west. Upon arriving in Britain, Ostorius faced immediate unrest. The western tribes, including the Silures and Ordovices in modern-day Wales, resisted Roman expansion. To prevent further uprisings, Ostorius began disarming the local population, a move that sparked further resistance.

One of Ostoriusís key objectives was to subdue Caratacus, who had fled west after the initial invasion. Caratacus became a symbol of British resistance and rallied tribes to his cause. In AD 51, Ostorius launched a campaign to capture him. The decisive battle took place in the Welsh hills, where Roman forces defeated Caratacusís forces despite the challenging terrain. Caratacus was captured and taken to Rome, where he was paraded before Emperor Claudius. Remarkably, Caratacusís bravery impressed the emperor, and he was allowed to live in peace.

Despite this victory, the western tribes continued to resist. The Silures in particular waged a guerrilla war against Roman forces, and Ostorius struggled to maintain control. He died in office in AD 52, leaving the western frontier insecure.

The Campaigns of Didius Gallus (AD 52-57)

Didius Gallus succeeded Ostorius Scapula and adopted a more cautious approach to governance. His focus was on maintaining Roman control rather than expanding it further. Gallus fortified existing positions and focused on keeping the peace, particularly in the west.

His governorship saw limited military activity, but he continued to face challenges from the Silures and other rebellious tribes. Gallusís tenure was relatively uneventful compared to his predecessors, but his efforts helped stabilize the province.

The Campaigns of Quintus Veranius (AD 57)

Quintus Veranius succeeded Didius Gallus but died shortly after taking office. Despite his short tenure, Veranius began preparations for a renewed campaign in Wales, targeting the Silures once again. His early death meant that these plans were not fully realized, and his successor, Suetonius Paulinus, would take up the task.

The Campaigns of Suetonius Paulinus (AD 58-60)

Suetonius Paulinus is best known for his campaign against the Druids in Anglesey (Mona), which he launched in AD 60. The Druids were a significant religious and political force in Britain, and Paulinus sought to eliminate their influence. His assault on Anglesey was brutal, with Roman forces destroying sacred sites and slaughtering the Druids.

However, while Paulinus was occupied in Wales, a major revolt broke out in the southeast, led by Queen Boudica of the Iceni. The revolt saw the destruction of several Roman towns, including Camulodunum, Londinium (London), and Verulamium (St Albans). Paulinus regrouped his forces and confronted Boudicaís army in a decisive battle, where the Romans achieved a crushing victory. Boudicaís revolt, though ultimately unsuccessful, forced the Romans to reconsider their policies in Britain.

The Campaigns of Vettius Bolanus (AD 69-71)

Following a period of instability in the Roman Empire, Vettius Bolanus was appointed governor of Britain during the Year of the Four Emperors. His governorship was marked by a more defensive approach. Bolanus focused on securing Roman positions and avoiding major confrontations with the northern tribes.

The Campaigns of Petillius Cerialis (AD 71-73)

Petillius Cerialis launched a series of campaigns in northern Britain, targeting the Brigantes, the largest tribe in the region. The Brigantes had previously been Roman allies, but internal conflicts led to rebellion. Cerialisís campaigns restored Roman control over the north and established several key forts.

The Campaigns of Julius Frontinus (AD 73-77)

Julius Frontinus focused on completing the conquest of Wales. He launched successful campaigns against the Silures and Ordovices, securing the region and establishing a network of forts to maintain control.

The Campaigns of Agricola (AD 77-84)

Gnaeus Julius Agricola is perhaps the most famous governor of Roman Britain. He launched a series of campaigns into Scotland, culminating in the Battle of Mons Graupius in AD 83. Agricolaís victory brought much of Scotland under Roman influence, though it was never fully incorporated into the province. Agricola also focused on Romanizing the local population, introducing Roman customs, language, and infrastructure.

Conclusion

The Roman invasion and subsequent occupation of Britain were gradual and complex processes, requiring sustained military campaigns over several decades. Each governor played a crucial role in expanding and consolidating Roman control, shaping the province's development. Despite challenges from both internal revolts and external threats, the Romans established a lasting legacy in Britain, influencing its culture, economy, and infrastructure for centuries to come.

The Roman invasion and subsequent occupation of Britain were gradual and complex processes, requiring sustained military campaigns over several decades. Each governor played a crucial role in expanding and consolidating Roman control, shaping the province's development. Despite challenges from both internal revolts and external threats, the Romans established a lasting legacy in Britain, influencing its culture, economy, and infrastructure for centuries to come.

The Roman Occupation of Britain: Life, Governance, and Legacy

Following the Roman invasion of Britain in AD 43, the province of Britannia became a key part of the Roman Empire for nearly four centuries. The occupation transformed Britainís political, social, and cultural landscape, introducing new systems of governance, infrastructure, and ways of life. The Roman influence reshaped the island, integrating it into the wider empire through trade, military presence, and Romanization. Despite enduring threats from native uprisings and external raids, the Romans maintained control through a combination of military force and administrative reforms. This occupation left a legacy that would endure long after the Romans withdrew in AD 410.

The Establishment of Roman Britannia

After the initial invasion, the Romans quickly moved to consolidate their control over the conquered territories. The province of Britannia was formally established, with its administrative capital at Camulodunum (modern Colchester). However, in AD 60, the provincial capital was moved to Londinium (modern London) after Boudicaís revolt devastated Camulodunum. Londinium became the center of Roman administration, trade, and governance for the remainder of the occupation.

The Roman provincial system introduced a hierarchical structure of governance. At the top was the governor, appointed by the emperor, who had both military and administrative authority. The governor was responsible for commanding the legions stationed in Britain, enforcing Roman law, and collecting taxes. Supporting the governor was a procurator, who managed the provinceís finances and ensured the flow of revenue to Rome.

The Romans also established a system of local governance by co-opting native elites. Tribal leaders who pledged loyalty to Rome were allowed to retain their positions and were granted Roman citizenship. This policy helped to secure local cooperation and reduce the likelihood of rebellion.

Military Presence in Roman Britain

The Roman occupation of Britain relied heavily on a strong military presence. The province was initially garrisoned by four legions, each consisting of approximately 5,000 soldiers. Over time, the number of legions was reduced to three, but they were supplemented by auxiliary troops recruited from across the empire.

The Roman occupation of Britain relied heavily on a strong military presence. The province was initially garrisoned by four legions, each consisting of approximately 5,000 soldiers. Over time, the number of legions was reduced to three, but they were supplemented by auxiliary troops recruited from across the empire.

The Roman army built a network of forts and roads to facilitate the movement of troops and supplies. Major forts were established at key locations, including Eboracum (York), Deva Victrix (Chester), and Isca Augusta (Caerleon). These military bases became centers of Roman culture and economic activity, often developing into towns.

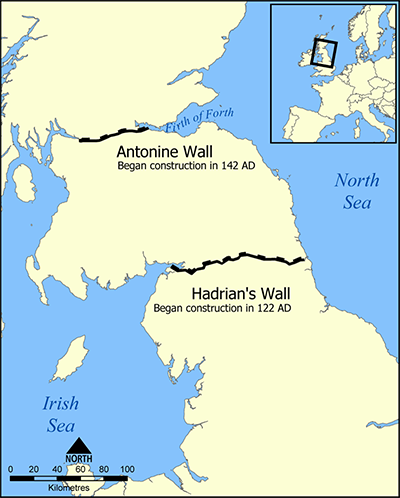

One of the most significant military constructions in Roman Britain was Hadrianís Wall, built during the reign of Emperor Hadrian in AD 122. The wall stretched for 80 Roman miles (73 modern miles) across northern England, from the River Tyne near Newcastle to the Solway Firth. Hadrianís Wall marked the northern boundary of the Roman Empire in Britain and was designed to control movement, prevent raids from northern tribes, and demonstrate Romeís power.

The wall consisted of a stone structure, with a ditch to the north and a military road to the south. Milecastles (small forts) were positioned at regular intervals along the wall, with larger forts such as Vindolanda and Housesteads providing accommodations for garrisoned troops. Hadrianís Wall became a symbol of Roman strength and remains one of the most iconic remnants of the Roman occupation.

Later, during the reign of Antoninus Pius, the Romans attempted to extend their control further north by building the Antonine Wall in modern Scotland. Constructed between AD 142 and 154, this turf wall stretched from the Firth of Forth to the Firth of Clyde. However, the Antonine Wall was abandoned after a few decades, and the Romans retreated to Hadrianís Wall, which remained the northern frontier for the rest of the occupation.

Urbanization and Infrastructure

The Roman occupation brought significant changes to Britainís infrastructure and urban landscape. The Romans introduced the concept of towns, or civitates, which became centers of administration, commerce, and culture. Towns were often built near military forts or along major roads and were laid out in a grid pattern, with a forum (marketplace) at the center.

Londinium became the most important city in Roman Britain, serving as the provincial capital and a major commercial hub. The city was equipped with typical Roman amenities, including bathhouses, temples, and an amphitheater. Other notable towns included Verulamium (St Albans), Corinium Dobunnorum (Cirencester), and Aquae Sulis (Bath), known for its Roman baths dedicated to the goddess Sulis Minerva.

The Romans built an extensive network of roads across Britain to facilitate the movement of troops and goods. Major roads, such as Watling Street and Fosse Way, connected key towns and forts, allowing for efficient communication and trade.

Economy and Trade

Roman Britain was integrated into the wider economy of the empire. The province exported goods such as grain, cattle, metals (particularly tin, lead, and silver), and wool. In return, Britain imported luxury items from other parts of the empire, including wine, olive oil, and fine pottery.

Roman villas, large country estates, became a common feature of the countryside. These estates were owned by wealthy Romanized Britons and were centers of agricultural production. Villas often featured elaborate mosaics, hypocaust heating systems, and private bathhouses, reflecting the wealth and status of their owners.

The introduction of Roman coinage also facilitated trade and economic activity. Coins minted in Britain, such as those produced at the Londinium mint, circulated throughout the province and beyond.

Roman Religion and Culture

The Romans introduced their religious beliefs to Britain, building temples dedicated to gods such as Jupiter, Mars, and Minerva. However, Roman religion often blended with local Celtic beliefs, creating unique syncretic practices. For example, the goddess Sulis, worshipped at Bath, was identified with the Roman goddess Minerva.

One of the most significant cultural changes was the introduction of Christianity. Although initially a minority religion, Christianity gained a foothold in Britain, particularly after Emperor Constantineís Edict of Milan in AD 313, which granted religious tolerance to Christians. By the fourth century, Christianity was well established in Britain, with bishops from British cities attending church councils on the continent.

Decline and Withdrawal

By the late fourth century, the Roman Empire faced increasing internal and external pressures. Barbarian invasions, economic difficulties, and political instability weakened the empire. In Britain, the Roman administration struggled to maintain control as troops were redeployed to defend other parts of the empire.

In AD 410, Emperor Honorius issued a letter to the cities of Britain, instructing them to look to their own defenses. This marked the official end of Roman rule in Britain. The withdrawal of Roman troops left the island vulnerable to raids from Saxons, Picts, and Irish tribes.

The Roman influence did not disappear overnight. Many aspects of Roman culture, law, and infrastructure remained, shaping the development of medieval Britain. The legacy of the Roman occupation can still be seen today in Britainís roads, place names, and archaeological sites.

Conclusion

The Roman occupation of Britain was a period of profound transformation. It brought new technologies, systems of governance, and cultural practices that reshaped the island's society and economy. Despite challenges from both internal revolts and external threats, the Romans established a lasting legacy that would influence Britain for centuries. Hadrianís Wall, Roman towns, and roads remain as enduring reminders of this period, reflecting the lasting impact of Roman rule on the history and development of Britain.

The Roman occupation of Britain was a period of profound transformation. It brought new technologies, systems of governance, and cultural practices that reshaped the island's society and economy. Despite challenges from both internal revolts and external threats, the Romans established a lasting legacy that would influence Britain for centuries. Hadrianís Wall, Roman towns, and roads remain as enduring reminders of this period, reflecting the lasting impact of Roman rule on the history and development of Britain.

Map of the Roman campaigns

Map of Hadrians Wall and Antonine Wall

Author: Simon Ellis

Date Published: 27th December 2024

Date Published: 27th December 2024