Queen Mary I – Quick Stats

Born: 18 February 1516

Her status was severely diminished when Henry VIII married Anne Boleyn in 1533. Mary was stripped of her title as princess and declared illegitimate. Forced to live separately from her mother, she endured emotional distress and political isolation.

Queen Mary I of England: The First Woman to Rule in Her Own Right

As a child, she was well-educated and displayed great intelligence, receiving instruction in Latin, Spanish, music, and theology. She was also deeply influenced by her mother’s strong Catholic beliefs, which would later define her reign.

Accession to the Throne

Upon Edward’s death in July 1553, Mary faced immediate opposition as Lady Jane Grey was declared queen. However, Mary acted swiftly, gathering an army of supporters, many of whom were discontented with Edward’s religious policies. Her popularity among the common people and the nobility, combined with Jane Grey’s lack of widespread support, led to Mary’s successful overthrow of Jane Grey’s brief nine-day reign. Mary entered London in triumph, marking the first time a woman had ascended the English throne in her own right.

Upon Edward’s death in July 1553, Mary faced immediate opposition as Lady Jane Grey was declared queen. However, Mary acted swiftly, gathering an army of supporters, many of whom were discontented with Edward’s religious policies. Her popularity among the common people and the nobility, combined with Jane Grey’s lack of widespread support, led to Mary’s successful overthrow of Jane Grey’s brief nine-day reign. Mary entered London in triumph, marking the first time a woman had ascended the English throne in her own right.

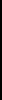

Upon her accession, Mary was determined to restore England to Roman Catholicism. She reversed Edward VI’s religious policies and reinstated Catholic practices, including mass and papal supremacy. Her government began persecuting Protestants who refused to convert, leading to widespread executions that earned her the infamous nickname “Bloody Mary”. Nearly 300 Protestants were burned at the stake for heresy, and many others fled to Protestant-friendly regions in Europe.

Early Life and Background

Queen Mary I was born on 18 February 1516 at the Palace of Placentia in Greenwich, England. She was the daughter of King Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, his first wife.

Queen Mary I was born on 18 February 1516 at the Palace of Placentia in Greenwich, England. She was the daughter of King Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon, his first wife.

Died: 17 November 1558

Mother: Catherine of Aragon

Father: Henry VIII

Husband: Philip II of Spain

Children: None

However, her early years were marked by political and familial turmoil, particularly after her father sought to annul his marriage to Catherine in pursuit of a male heir.

Successor : Elizabeth I

Predecessor : King Edward VI

Despite these hardships, Mary remained devoted to her faith and refused to renounce Catholicism, even under intense pressure from Henry and his advisors.

The Struggle for Legitimacy

After Anne Boleyn’s execution in 1536 and Henry’s subsequent marriages, Mary’s position remained uncertain.

After Anne Boleyn’s execution in 1536 and Henry’s subsequent marriages, Mary’s position remained uncertain.

Her household was drastically reduced, and she was eventually compelled to recognize her father as the Supreme Head of the Church of England and acknowledge her parents' marriage as unlawful.

She was eventually reinstated into the succession through the Third Succession Act of 1544, which placed her after her younger half-brother, Edward VI, and her half-sister, Elizabeth.

However, her legitimacy was never fully secure, and she continued to face challenges from Protestant factions within the court.

Marriage to Philip II of Spain

In 1554, Mary married Philip II of Spain, hoping to strengthen England's ties with Catholic Europe and secure an heir to continue Catholic rule. Philip was a powerful ruler, and the marriage was meant to create a strong Anglo-Spanish alliance. However, the union was deeply unpopular among the English people, who feared English subjugation to Spanish interests. Parliament resisted granting Philip significant power, and he remained a largely distant figure in English politics.

In 1554, Mary married Philip II of Spain, hoping to strengthen England's ties with Catholic Europe and secure an heir to continue Catholic rule. Philip was a powerful ruler, and the marriage was meant to create a strong Anglo-Spanish alliance. However, the union was deeply unpopular among the English people, who feared English subjugation to Spanish interests. Parliament resisted granting Philip significant power, and he remained a largely distant figure in English politics.

Death and Legacy

Mary I died on 17 November 1558, possibly from ovarian cancer or influenza. She was succeeded by her half-sister, Elizabeth I, who swiftly reversed many of Mary’s Catholic policies and firmly established Protestantism in England. Elizabeth's reign would become one of the most celebrated in English history, in stark contrast to Mary’s.

Mary I died on 17 November 1558, possibly from ovarian cancer or influenza. She was succeeded by her half-sister, Elizabeth I, who swiftly reversed many of Mary’s Catholic policies and firmly established Protestantism in England. Elizabeth's reign would become one of the most celebrated in English history, in stark contrast to Mary’s.

She continued practicing Catholicism in private, which led to tensions between her and the Protestant authorities. As Edward’s health declined, he and his advisors attempted to exclude Mary from the succession in favor of his Protestant cousin, Lady Jane Grey, in an effort to prevent England from reverting to Catholic rule.

Mary's attempts to conceive were unsuccessful, leading to speculation that she suffered from reproductive health issues. In 1555, she experienced what she believed to be a pregnancy, but no child was born. This phantom pregnancy was a source of great disappointment and ridicule, and it only further weakened her position. Philip, realizing that England was of limited use to his ambitions, spent little time in the country, exacerbating Mary’s sense of isolation.

Economic and Political Challenges

Mary’s reign faced severe economic difficulties, including inflation, harvest failures, and taxation issues. Her financial policies, such as heavy taxation and coin debasement, worsened economic instability. England also suffered from food shortages due to poor harvests, leading to widespread discontent.

Mary’s reign faced severe economic difficulties, including inflation, harvest failures, and taxation issues. Her financial policies, such as heavy taxation and coin debasement, worsened economic instability. England also suffered from food shortages due to poor harvests, leading to widespread discontent.

Following the death of Henry VIII in 1547, Edward VI, a staunch Protestant, took the throne at the age of nine. His reign saw sweeping religious reforms that sought to establish Protestantism firmly in England, which Mary vehemently opposed.

Depiction of John Rogers the first Protistant burned at the stake

Her alliance with Spain ultimately led England into a war with France, culminating in the devastating loss of Calais in 1558. Calais had been England’s last remaining territory on the European mainland, and its loss was a severe blow to national pride. Mary reportedly mourned the loss deeply, claiming that when she died, the name "Calais" would be found inscribed on her heart.

Though her reign lasted only five years, Mary I’s rule remains one of the most controversial in English history. Her efforts to restore Catholicism ultimately failed, and her persecution of Protestants left a lasting stain on her legacy. However, her reign set a precedent for female monarchs in England. As the first woman to rule England in her own right, she paved the way for future queens such as Elizabeth I, Queen Victoria, and Elizabeth II.

Historians continue to debate her reign, with some arguing that she was a determined ruler who sought to restore England’s traditional religious identity, while others emphasize the brutality of her policies. Despite her failures, Mary’s rule marked a critical period in English history, illustrating the deep religious divisions that would continue to shape the nation for decades.

Conclusion

Queen Mary I’s rule was one of turbulence, religious strife, and unfulfilled ambitions. Despite her efforts, Protestantism would ultimately triumph in England under Elizabeth I. However, her reign remains a crucial chapter in the Tudor dynasty, reflecting the fierce struggles over religion and power that shaped England’s future. While she is often remembered for the persecution of Protestants, her reign was also significant in demonstrating that a woman could successfully rule England, setting an important precedent for the future.

Queen Mary I’s rule was one of turbulence, religious strife, and unfulfilled ambitions. Despite her efforts, Protestantism would ultimately triumph in England under Elizabeth I. However, her reign remains a crucial chapter in the Tudor dynasty, reflecting the fierce struggles over religion and power that shaped England’s future. While she is often remembered for the persecution of Protestants, her reign was also significant in demonstrating that a woman could successfully rule England, setting an important precedent for the future.