Oliver Cromwell – Quick Stats

Born: April 25, 1599, Huntingdon, England

Oliver Cromwell: The Rise and Rule of England’s Lord Protector

He was the son of Robert Cromwell and Elizabeth Steward. His family had strong Puritan leanings, which influenced his deep Protestant faith and later political convictions. His early life was marked by religious devotion, personal struggles, and financial instability.

In 1620, he married Elizabeth Bourchier, the daughter of a wealthy merchant family, which helped stabilize his financial standing. Together, they had several children, and Elizabeth remained a steadfast supporter throughout his tumultuous career.

Died: September 3, 1658, Whitehall, London

Mother: Elizabeth Cromwell (née Steward)

Father: Robert Cromwell

Wife: Elizabeth Bourchier

Children:

Bridget Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell Jr

Robert Cromwell

Early Life and Background

Oliver Cromwell was born on April 25, 1599, in Huntingdon, England, into a moderately prosperous gentry family.

Oliver Cromwell was born on April 25, 1599, in Huntingdon, England, into a moderately prosperous gentry family.

Before entering the national political stage, Cromwell lived as a country gentleman, struggling with debt and personal setbacks. However, his deepening Puritan faith and growing dissatisfaction with the monarchy would soon propel him into political activism.

Rise to Power in the English Civil War

By the late 1630s, tensions between King Charles I and Parliament had escalated, primarily over issues of taxation, religion, and royal authority. Charles I’s attempts to rule without Parliament for over a decade had created widespread resentment.

By the late 1630s, tensions between King Charles I and Parliament had escalated, primarily over issues of taxation, religion, and royal authority. Charles I’s attempts to rule without Parliament for over a decade had created widespread resentment.

Cromwell, deeply opposed to what he saw as the king’s abuse of power and his inclination toward Catholic-leaning policies, entered politics as a Member of Parliament for Cambridge in 1628 and later in the Long Parliament of 1640.

Cromwell’s rise in military and political prominence coincided with growing dissatisfaction toward Charles I. Even after the war ended, tensions persisted over how England should be governed. Cromwell played a crucial role in the trial and execution of Charles I in 1649, marking the first and only execution of an English king by his own people. With the monarchy abolished, England was declared a republic under the Commonwealth, setting the stage for Cromwell's unprecedented rise to power.

The Commonwealth and Cromwell’s Leadership

Following Charles I’s execution, England became a republic governed by the Rump Parliament and later the Council of State. Cromwell initially worked within this framework but grew frustrated with the inefficiency and corruption of Parliament. In 1653, he forcibly dissolved the Rump Parliament in an event that famously saw him declare, "You have sat too long for any good you have been doing!" With support from the army, he was appointed Lord Protector—a position that effectively made him ruler of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Following Charles I’s execution, England became a republic governed by the Rump Parliament and later the Council of State. Cromwell initially worked within this framework but grew frustrated with the inefficiency and corruption of Parliament. In 1653, he forcibly dissolved the Rump Parliament in an event that famously saw him declare, "You have sat too long for any good you have been doing!" With support from the army, he was appointed Lord Protector—a position that effectively made him ruler of England, Scotland, and Ireland.

Richard Cromwell

Similarly, Cromwell led campaigns in Scotland, defeating the forces of Charles II at the Battle of Dunbar (1650) and Worcester (1651). His victories cemented English control over the British Isles but left a legacy of deep-seated animosity in both nations. While his military successes expanded England's influence, the brutality with which he enforced his rule earned him as many enemies as admirers.

Henry Cromwell

Elizabeth Cromwell

Mary Cromwell

Successor: Richard Cromwell (Lord Protector)

Predecessor: King Charles I

Cromwell attended Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, a Puritan-founded institution, but left without earning a degree following his father’s death in 1617. His subsequent years were spent navigating personal difficulties, including bouts of depression and an identity crisis, as he sought to align his life with his religious convictions.

When civil war erupted in 1642, Cromwell quickly distinguished himself as a military leader. Despite having no formal military training, he proved to be a brilliant strategist and tactician.

He formed the "Ironsides," a disciplined cavalry force that played a key role in several battles, including the decisive Battle of Marston Moor (1644) and the Battle of Naseby (1645), which sealed the fate of the Royalists. His emphasis on merit over noble birth in military leadership revolutionized England’s armed forces and contributed to Parliament's eventual victory.

As Lord Protector, Cromwell ruled with near-monarchical authority but rejected the title of king, believing that a return to monarchy would be a betrayal of the ideals fought for in the Civil War. His government promoted religious tolerance for Protestants, reformed the legal system, and sought to strengthen England’s economy and military. Under his leadership, England emerged as a dominant naval power, securing victories against Spain and the Dutch Republic, particularly through the Navigation Acts, which boosted English trade.

After the Restoration, Cromwell’s body was exhumed, posthumously executed, and displayed as an act of retribution by Royalists. Despite this, his legacy remains complex. Some view him as a champion of liberty and Protestantism, while others see him as a ruthless dictator who suppressed opposition through military might.

Regardless of perspective, Cromwell was instrumental in shaping England’s political evolution, challenging the divine right of kings and laying the foundations for constitutional government. His impact continues to spark debate among historians, making him one of the most controversial figures in British history. His rule set precedents that would influence the later development of constitutional monarchy and parliamentary democracy in Britain, ensuring his place in history as both a revolutionary leader and a deeply polarizing figure.

However, his rule also had an authoritarian streak. He dismissed parliaments when they failed to align with his vision and relied on military support to enforce his policies. While he maintained a degree of order, his rule was met with resistance, particularly from those who had hoped for a more democratic government following the monarchy’s fall.

The Conquest of Ireland and Scotland

Cromwell’s rule is often criticized for his brutal military campaigns in Ireland and Scotland. In 1649, he led a campaign to crush Irish resistance, viewing it as both a Catholic and Royalist stronghold. The sieges of Drogheda and Wexford were particularly infamous, as Cromwell’s forces massacred thousands of soldiers and civilians. His harsh policies led to the confiscation of Irish land, furthering resentment that lasted for generations and leaving a lasting scar on Anglo-Irish relations.

Cromwell’s rule is often criticized for his brutal military campaigns in Ireland and Scotland. In 1649, he led a campaign to crush Irish resistance, viewing it as both a Catholic and Royalist stronghold. The sieges of Drogheda and Wexford were particularly infamous, as Cromwell’s forces massacred thousands of soldiers and civilians. His harsh policies led to the confiscation of Irish land, furthering resentment that lasted for generations and leaving a lasting scar on Anglo-Irish relations.

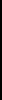

The Deathmask Of Oliver Cromwell

Francis Cromwell

Domestic Policies and Reforms

Cromwell’s rule was marked by efforts to reform English society along Puritan lines. He enforced strict moral laws, shutting down theaters, banning certain forms of entertainment, and imposing religious observance. Taverns, gambling, and festivities such as Christmas celebrations were curtailed or banned altogether. His attempts to create a "Godly nation" were unpopular among many, leading to growing dissatisfaction.

Cromwell’s rule was marked by efforts to reform English society along Puritan lines. He enforced strict moral laws, shutting down theaters, banning certain forms of entertainment, and imposing religious observance. Taverns, gambling, and festivities such as Christmas celebrations were curtailed or banned altogether. His attempts to create a "Godly nation" were unpopular among many, leading to growing dissatisfaction.

While he promoted religious freedom for Protestants, he was intolerant toward Catholics, enforcing harsh measures against them. However, he allowed Jews to return to England in 1656 after their expulsion in 1290, an act seen by some as a step toward greater religious tolerance.

Economically, Cromwell encouraged trade and expanded England’s colonial influence, particularly in the Caribbean. His government also laid the groundwork for England’s future as a global power, increasing the country's international standing through military victories and commercial policies that bolstered trade.

Death and Legacy

Oliver Cromwell died on September 3, 1658, at Whitehall, London, likely from complications of malaria and kidney disease. He was succeeded by his son, Richard Cromwell, who lacked his father’s leadership skills and was unable to maintain control. Within two years, the monarchy was restored under Charles II in 1660, bringing an end to the Commonwealth.

Oliver Cromwell died on September 3, 1658, at Whitehall, London, likely from complications of malaria and kidney disease. He was succeeded by his son, Richard Cromwell, who lacked his father’s leadership skills and was unable to maintain control. Within two years, the monarchy was restored under Charles II in 1660, bringing an end to the Commonwealth.