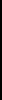

King Harold II Godwinson - Quick Stats

Born: c 1022 AD

King Harold II: The Last Anglo-Saxon King of England

King Harold II, also known as Harold Godwinson, occupies a unique and poignant position in English history as the final Anglo-Saxon monarch. His short-lived reign in 1066 was marked by extraordinary challenges and a chain of dramatic events, culminating in his death at the Battle of Hastings. This defeat signaled the end of Anglo-Saxon England and ushered in Norman rule under William the Conqueror. Harold’s life, brimming with ambition, political acumen, and military prowess, reflects the dynamic and transitional period in England's history during the 11th century.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Harold was born around 1022 into one of the most powerful noble families in England. His father, Godwin, Earl of Wessex, was a key ally of King Cnut, the Danish ruler who controlled England during Harold’s early years. This close association with royalty allowed Harold to grow up in an environment steeped in political intrigue, power struggles, and courtly diplomacy. Harold’s mother, Gytha Thorkelsdóttir, came from a prominent Danish noble lineage, further enhancing the family’s influence.

Harold was born around 1022 into one of the most powerful noble families in England. His father, Godwin, Earl of Wessex, was a key ally of King Cnut, the Danish ruler who controlled England during Harold’s early years. This close association with royalty allowed Harold to grow up in an environment steeped in political intrigue, power struggles, and courtly diplomacy. Harold’s mother, Gytha Thorkelsdóttir, came from a prominent Danish noble lineage, further enhancing the family’s influence.

Harold was groomed for leadership from an early age. His education emphasized the skills of governance, military strategy, and diplomacy, all essential attributes for a man destined to navigate the turbulent waters of 11th-century English politics. By the time of Godwin’s death in 1053, Harold had established himself as a capable and ambitious leader, succeeding his father as Earl of Wessex. This position gave him control over vast lands and resources, solidifying his role as one of the most powerful figures in England.

The Battle of Stamford Bridge

Harold responded with extraordinary speed, leading his army on a forced march from London to Yorkshire in just four days. On September 25, 1066, his forces confronted Hardrada and Tostig at the Battle of Stamford Bridge. In a fierce and bloody encounter, the English army achieved a decisive victory, killing both Hardrada and Tostig. This triumph demonstrated Harold’s exceptional leadership and the discipline of his troops, but it came at a high cost. The army was exhausted and weakened, a factor that would prove critical in the battles to come.

In the 1060s, Harold’s military campaigns against Wales showcased his skill as a commander. Collaborating with his brother Tostig, Harold led a series of decisive raids that culminated in the defeat of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, the Welsh ruler. This victory not only brought peace to the Welsh borders but also burnished Harold’s reputation as a formidable military leader, earning him the loyalty and respect of both the English nobility and common soldiers.

Children: Gytha of Wessex

Godwin

Harold

Magnus

Gunhild of Wessex

Ulf

Edmund

Godwin

Harold

Magnus

Gunhild of Wessex

Ulf

Edmund

Wives: Edith the Fair

Edith of Mercia

Edith of Mercia

Father: Godwin, Earl of Wessex

Mother: Gytha Thorkelsdóttir

Died: 4th October 1066 AD Battle of Hastings

Despite these differences, Harold became one of Edward’s most trusted advisors, a testament to his political skill and pragmatism. As Edward grew older and increasingly withdrew from the day-to-day governance of the kingdom, Harold assumed a larger role in managing the affairs of state. By the mid-1060s, he was effectively the most powerful man in England, often acting as a de facto ruler in Edward’s stead.

The question of Edward’s succession loomed large during this period. Childless and aging, Edward’s intentions regarding his successor were unclear, and conflicting accounts have survived. Norman sources claim that Edward promised the throne to William, Duke of Normandy, while Anglo-Saxon chronicles assert that Edward favored Harold as his heir. Harold’s visit to Normandy in the early 1060s, during which he allegedly swore an oath of allegiance to William, remains one of the most controversial and debated events of his life.

The Succession Crisis and Harold’s Coronation

When Edward the Confessor died on January 5, 1066, he left behind a kingdom without a direct heir. On his deathbed, Edward is said to have entrusted the kingdom to Harold, a claim supported by the Witenagemot, the council of nobles and clergy. Acting swiftly to secure his position, Harold was crowned king on January 6, 1066, in a ceremony at Westminster Abbey. His coronation, however, was far from uncontested.

When Edward the Confessor died on January 5, 1066, he left behind a kingdom without a direct heir. On his deathbed, Edward is said to have entrusted the kingdom to Harold, a claim supported by the Witenagemot, the council of nobles and clergy. Acting swiftly to secure his position, Harold was crowned king on January 6, 1066, in a ceremony at Westminster Abbey. His coronation, however, was far from uncontested.

The Norman Invasion and the Battle of Hastings

While Harold was preoccupied in the north, William of Normandy launched his long-planned invasion in the south. Landing at Pevensey on September 28, 1066, William quickly established a base of operations and began advancing inland. Harold, despite the fatigue of his army, chose to march south without delay, covering nearly 200 miles in just two weeks.

Harold’s claim to the throne was immediately challenged by two powerful rivals. William of Normandy asserted that Edward had promised him the crown and accused Harold of breaking his earlier oath of support. Meanwhile, Harald Hardrada, King of Norway, invoked an agreement among earlier Scandinavian rulers to justify his own claim to the English throne. These competing claims set the stage for one of the most tumultuous years in English history

Harold’s Reign and Military Challenges

Harold’s nine-month reign was marked by relentless conflict and extraordinary tests of his leadership. Forced to defend his crown on multiple fronts, Harold demonstrated remarkable resilience, strategic acumen, and personal bravery. However, the sheer scale of the challenges he faced ultimately proved insurmountable.

Harold’s nine-month reign was marked by relentless conflict and extraordinary tests of his leadership. Forced to defend his crown on multiple fronts, Harold demonstrated remarkable resilience, strategic acumen, and personal bravery. However, the sheer scale of the challenges he faced ultimately proved insurmountable.

The Battle of Fulford

The first major crisis arose in September 1066, when Harald Hardrada, allied with Tostig Godwinson, Harold’s estranged brother, launched an invasion in northern England. On September 20, their forces defeated an English army led by the northern earls Edwin and Morcar at the Battle of Fulford. This victory allowed the invaders to establish a stronghold near York, threatening Harold’s control over the north.

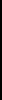

The climactic Battle of Hastings took place on October 14, 1066. Harold’s forces, consisting of housecarls (professional soldiers) and fyrd (levied militia), adopted a strong defensive position on Senlac Hill. The Norman army, a mix of infantry, cavalry, and archers, employed a combination of direct assaults and feigned retreats to break the English shield wall. After hours of intense combat, the English line finally gave way. According to tradition, Harold was killed by an arrow to the eye, though accounts of his death vary. His fall marked the collapse of Anglo-Saxon resistance and the beginning of Norman rule.

Predecessor: Edward the Confessor

Successor: William the Conqueror

Relationship with Edward the Confessor

Harold’s relationship with Edward the Confessor was a nuanced and evolving one. Edward, who had spent many years in exile in Normandy before ascending to the English throne, maintained strong ties to Norman culture. This preference for Norman advisors often put him at odds with Harold’s Anglo-Saxon family, which represented the traditional English elite.

Harold’s relationship with Edward the Confessor was a nuanced and evolving one. Edward, who had spent many years in exile in Normandy before ascending to the English throne, maintained strong ties to Norman culture. This preference for Norman advisors often put him at odds with Harold’s Anglo-Saxon family, which represented the traditional English elite.

Harold’s Personal Life and Legacy

Harold’s personal life was as complex as his political career. His long-term relationship with Edith the Fair, also known as Edith Swanneck, produced several children, including Godwin, Edmund, Magnus, Gunhild, and Gytha. Edith is famously said to have identified Harold’s body after the Battle of Hastings by recognizing private marks on his body. Harold also formally married Ealdgyth, the widow of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, likely to secure alliances with powerful Welsh factions. At the time of Harold’s death, Ealdgyth was pregnant, but the fate of their child remains uncertain.

Harold’s personal life was as complex as his political career. His long-term relationship with Edith the Fair, also known as Edith Swanneck, produced several children, including Godwin, Edmund, Magnus, Gunhild, and Gytha. Edith is famously said to have identified Harold’s body after the Battle of Hastings by recognizing private marks on his body. Harold also formally married Ealdgyth, the widow of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, likely to secure alliances with powerful Welsh factions. At the time of Harold’s death, Ealdgyth was pregnant, but the fate of their child remains uncertain.

After Harold’s death, his family faced persecution and exile under Norman rule. His daughter Gytha fled to the Kievan Rus’, where she married Vladimir II Monomakh, Grand Prince of Kiev. Through this union, Harold’s bloodline continued in Eastern Europe, influencing royal dynasties far from the land he once ruled.

Legacy

Harold’s reign, though brief, was a turning point in English history. His defeat at Hastings marked the end of the Anglo-Saxon era, a period characterized by a unique blend of Germanic and Christian traditions. The Norman Conquest brought profound changes to England, including the introduction of feudalism, the reshaping of the English aristocracy, and significant cultural shifts.

Harold’s reign, though brief, was a turning point in English history. His defeat at Hastings marked the end of the Anglo-Saxon era, a period characterized by a unique blend of Germanic and Christian traditions. The Norman Conquest brought profound changes to England, including the introduction of feudalism, the reshaping of the English aristocracy, and significant cultural shifts.

Despite his ultimate failure, Harold is remembered as a courageous and capable leader who faced overwhelming odds with determination and resolve. For many, he symbolizes the resilience of Anglo-Saxon England, standing as a testament to a bygone era of independence and tradition. Historians continue to debate the significance of his reign, often portraying him as a tragic figure whose potential was cut short by forces beyond his control.

Conclusion

King Harold II’s life and reign encapsulate a moment of profound change in English history. As the last Anglo-Saxon king, he represents the end of an epoch and the dawn of a new age under Norman rule. His courage, leadership, and tragic fall continue to resonate as a compelling narrative of ambition, loyalty, and the inexorable tides of history. Harold’s story remains a vivid reminder of the complexities and fragility of power in a world shaped

King Harold II’s life and reign encapsulate a moment of profound change in English history. As the last Anglo-Saxon king, he represents the end of an epoch and the dawn of a new age under Norman rule. His courage, leadership, and tragic fall continue to resonate as a compelling narrative of ambition, loyalty, and the inexorable tides of history. Harold’s story remains a vivid reminder of the complexities and fragility of power in a world shaped

Bayeux Tapestry depicting King Harold II being shot in the eye with an arrow